Why the emperor of sustainable fashion is as naked as ever

And what the apparel industry needs to do now if they are serious about sustainability

Behold your emperor and his sustainable vestments!

Imagine a world where creators of cloth live in harmony with all creatures big and small; where every garment comes from a community that benefits from its very existence, just as you benefit from wearing it.

In this world, no one suffers to clothe you. All the riches of these traceable textile treasures are shared fairly among growers, makers, and designers. Clothing—ever more beautiful, comfortable, and durable—is the stuff of legends passed through the generations.

Behold, loyal consumers, the majesty of your emperor, Sustainable Fashion [trumpets blaring] reigning proud across the land!

That dude is naked, and he’s not our emperor

By now you’re likely cringing with cynicism. You and I both know that world is the stuff of make-believe fairy tales. Oh, and of apparel sector sustainability reports, too.

The human and more-than-human suffering at the hands of industrialized fashion and apparel has been well documented for centuries and has only grown worse as the sector grows—by about 186 billion new garments a year1.

I won’t rehash those issues—others do a fine job of that. For example, The Crisps do yeoman’s work on the technical and regulatory pitfalls of greenwash in fashion; and Pluriversal Planet exposes the intergenerational root causes of issues plaguing industry more broadly.

These issues are so well worn that the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) is quoted in a piece examining them, The Emperor is Naked… in 2012!

It is not for lack of recycling the issues that we are where we are.

Sustainable transformation is not a tweak

Instead of reupholstering the problem, I’ll do a reality check, or rather a Matereality-check2. You’ll see an apparel company’s stated purpose, how they earn revenue, and what is required instead for the industry to serve life, versus serving that naked, soul-sucking, and sorely unsustainable emperor.

And I’ll offer guidance about what companies and individuals can do about it, now.

The transformation required is not a tweak, it is a fundamental retooling of the business model. Although leading apparel companies are using the words “business model transformation”, as you’ll see, things are still stuck in the tweak phase. “Transformation” that makes the lion’s share of revenue from the same harmful business practices as 20 years ago is not transformation. “Transformation” that doesn’t touch shareholder primacy is also not transformation.

To illustrate the challenges and possibilities, I’ll use the public disclosures of global apparel giant H&M. I could pick on any one of their sector peers, but since they put themselves forward as leaders—signalling circularity and even regeneration—and since I already did a benchmarking on them back in March 2020 for a letter I wrote to BlackRock’s Larry Fink (he still hasn’t replied but I suppose things got hectic around then…), I thought I’d take a fresh look at them.

To be clear, I’m not here to promote hair shirts and sack cloth. I get that we need stuff, that clothing is essential, that fashion can be inspiring, and that there is no one way to get dressed in the morning, or get comfy under the covers at night. But I also believe that industry needs to serve life, not the other way around.

The real transformational options may seem crazy at first, but the alternative—sustainability as usual—is by far the crazier choice, as will become clear with the company’s own data, in the context of reality.

The concept of Matereality is about asking:

What needs to be true for the apparel industry to serve life?

How is the industry undermining life today?

What changes can the industry make right now to transform in service of life?

Seasoned industry sojourner/real life spinster at your service

Having convened the first live conversation between one of the most feared anti-sweatshop activists and a global retail giant nearly 20 years ago; having witnessed the birth (and now palliative rebranded state of) the SAC’s Higg Index3 which started measuring new clothes for the naked emperor back in 2012; having seen industrial sock knitting factories on the heels of touring monoculture plantations; in other words, having had more than a few fashion industry adventures during two decades in mainstream ESG consulting with some of the world’s largest manufacturers and retailers, I’ve seen behind the curtain.

More importantly, as a craftsperson I have deep respect for the soul of cloth, which feels absent from industry, at our peril. Designing, spinning, knitting, weaving, and creating garments from scratch since the 1970s, using diverse materials ranging from local wool that I met “on-the-hoof” to imported silk, from recycled PET to pet fur, I know my warp from my weft.

I have felt the power of intergenerational and intercultural cloth-making up close and personal, extending far beyond the maker’s hands and the wearer’s closet. And I’ve seen that power marginalized, commoditized, co-opted, and rebranded.

It’s these industry and grassroots level perspectives that bring me to do this work in service of something that truly serves life.

Not a “gotcha” — an “I got ya”

I’m not aiming to take anyone down here. Rather I’m recommending we lift ourselves up so we can get on with the business of thriving. We’ve been so swaddled in extraction and distraction, making light of retail therapy while wondering how come we’re fraying at the edges and need so much therapy in the first place.

In some ways what follows is run-of-the-mill sustainability myth busting. As noted, it’s no great secret that systemic issues persist in spite of corporate claims to the contrary.

I’ll offer an added twist: strategic recommendations for the needed transformation. I propose specific choices and metrics that apparel industry players can apply now to create real change.

It’s easy to say “Transformation!”, but it’s not easy to leave behind the known structures and norms and chart a truly transformational course. To help with this, I’ll provide touchstones of reality—real-world industry data points—to help you gather your courage for those moments when you wonder if it’s maybe better to let things keep going as they are.

With the industry data and disclosures below, you will see for yourself how even “leadership” in sustainable apparel is nowhere close to serving life. It’s still firmly pointed in the wrong direction, and proudly so.

And you can see choices to transform towards a life-affirming approach. It is a big leap. But if you are ready, I got ya!

On that note, let’s head on into the Matereal World and see what H&M is made of, and what needs to be true to clothe us like our life depends on it. Since it does.

Spinning virgin raw material into shareholder returns

According to its website, H&M is a global family of brands and businesses that “make it possible for customers around the world to express themselves through fashion and design in a sustainable way.”4

I’ll assume by sustainable they mean, at the very least, not undermining life. Sounds good so far. So how do they generate revenue?

They don’t give a clear breakdown of revenue sources that I could find, just overall sales figures aggregating their myriad brands and channels.

They do have a Sustainable Finance Framework5 which sounds promising, but on a deeper read it doesn’t deliver. I don’t have time to follow all the money in there. But I did this before, for a leading ethical investment fund—

—and I have no reason to believe this will be better. That’s another story, but the short version is: all the green finance mechanisms in the world are not restoring ecosystems and making humans healthier, nor are they designed to do so. The investment professionals who commented on that piece only deepened my concerns.

Please comment or get in touch directly if you know otherwise. I will gladly edit and publish a retraction. I would be *delighted* to learn of apparel finance efforts that are actually financing truly sustainable activities in global firms.

It is tempting to see the list of “Regenerative and/or transformative projects for key materials” as progress towards this, noted on page 33 of the 2022 Sustainability Disclosure6. For instance, the company states:

— We increased our share of recycled or other more sustainably sourced materials to 84%, including 23% recycled materials. We are introducing regenerative farming practices as part of our materials roadmap, including already placing orders for regenerative cotton in 2023 — see right.

These are no doubt true facts. Corporate legal counsel reviews these types of ESG documents carefully before they’re released. And they are not bad things in and of themselves. But putting on a Matereality lens, imagine if these same facts were worded thus:

— More than 75% of our raw materials are virgin; our (growing!) company created the (increasing!) demand for their existence. The vast majority of our natural fibers are produced through degenerative practices, so we’re writing things down in our materials roadmap that reflect ways of growing that have been practiced for centuries but which business models like ours stamped out in favour of mass commoditization, cheap labour, and predictability, in service of shareholder returns — see right.

You can see why I’m not jumping up and down with glee at this “progress”.

Back to the Sustainable Finance Framework in which they have a robust and detailed materiality assessment to inform their vision, where they state, “Sustainability is business critical, not only to fulfil our business idea, but also to meet evolving customer expectations and to ensure we future proof our business (page 3).”

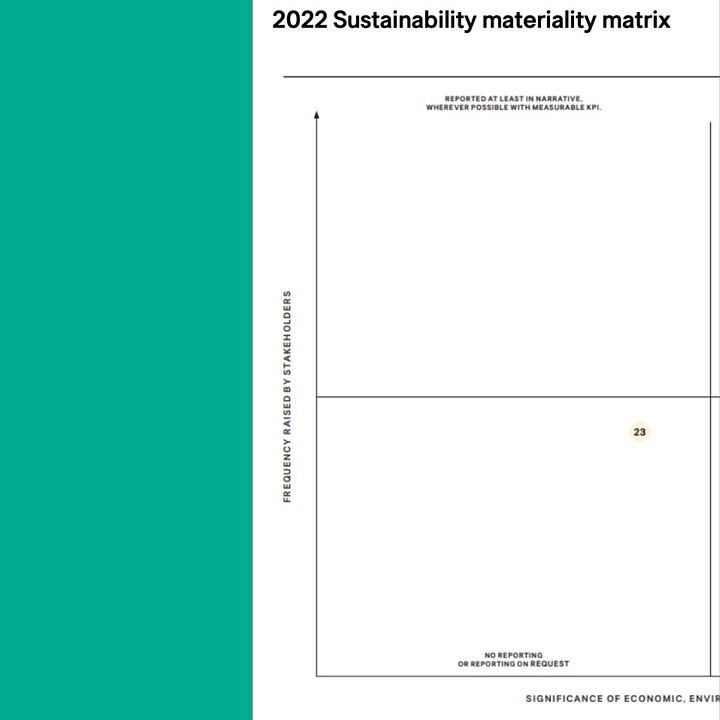

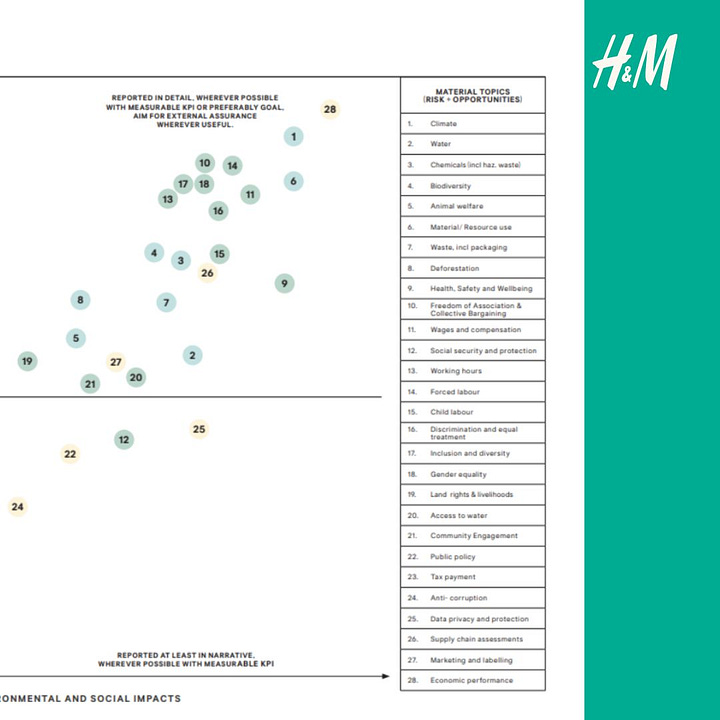

Below is that tool that H&M purports to help future proof their business—a materiality matrix with the 28 issues7 that stakeholders frequently mentioned as having significant environmental or social impact, from climate to community engagement, animal welfare to wages, etc.

Readers of the Matereal World will by now recognize such an assessment as a tall tale, full of sound and fury, told by well paid consultants, signifying nothing.

If their materiality assessment actually signified something, then the “most material issues” would be evident in how the company generates value. It would not be connected to a list of uphill-battles to get regenerative practices in place, and barely implemented initiatives that suggest things will change “over there”, “in the future”.

Shareholder primacy rules

As usual with a materiality assessment, they came up with a long list of interconnected issues without mentioning the primacy of shareholder returns, which is an obvious problem underpinning many of the material issues.

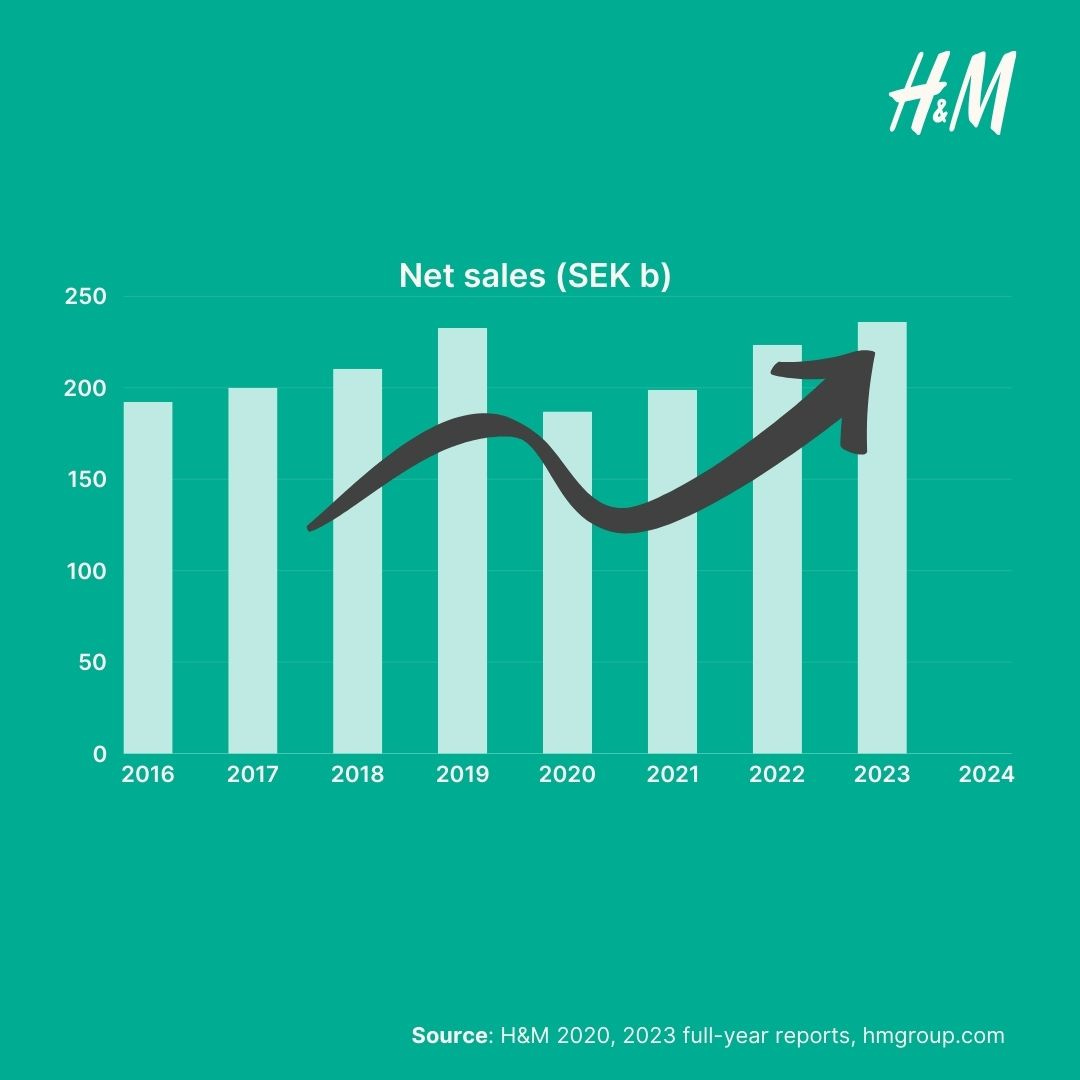

We don’t even need to follow the money to see what H&M plans do to, to make more of it for shareholders. In the opening remarks in their most recent investor earnings call8, outgoing CEO Helena Helmersson notes their priorities:

Our focus on cost control, profitability, and improved inventory productivity also contributed to increased cash flow, that is, financing and increased reinvestment in the business.

For many consumers 2023 was marked by lower purchasing power because of high inflation and high interest rates. Despite this, our net sales in comparable markets increased in relation to 2022.

She goes on to mention their investment in—and growth of—lifestyle brands, sports, beauty and home, as well as their portfolio brands.

Let’s not dwell on the detached reference to people’s lower purchasing power, which thank goodness H&M was able to weather with increased sales of cheap stuff to the downtrodden masses. Sheesh. Forget the soul of cloth. How about basic compassion? Helmersson notes that she stepped down for personal reasons.9 Maybe she was trying to make real change but the pressure for financial growth was too persistent? (I’m guessing. And having flashbacks to Danone’s former CEO, Emmanuel Faber10.)

For the keen listener, there is a kind of “last but not least” reference during the earnings call to Sellpy, the online secondhand retailer. But so far there is little to suggest this is a major revenue generator.

They talk a lot about “circular business models” across their ESG disclosures (and briefly with investors in the call referenced above). But to build on the adage “the map is not the territory,” the diagram is not the business model. Unless the cool diagram represents the way a company actually generates value, it’s just a cool diagram.

Mentions of circular business models aside, shareholder value seems to be the main objective, as the recent share buy-back11 suggests. The material issues can get in line behind that.

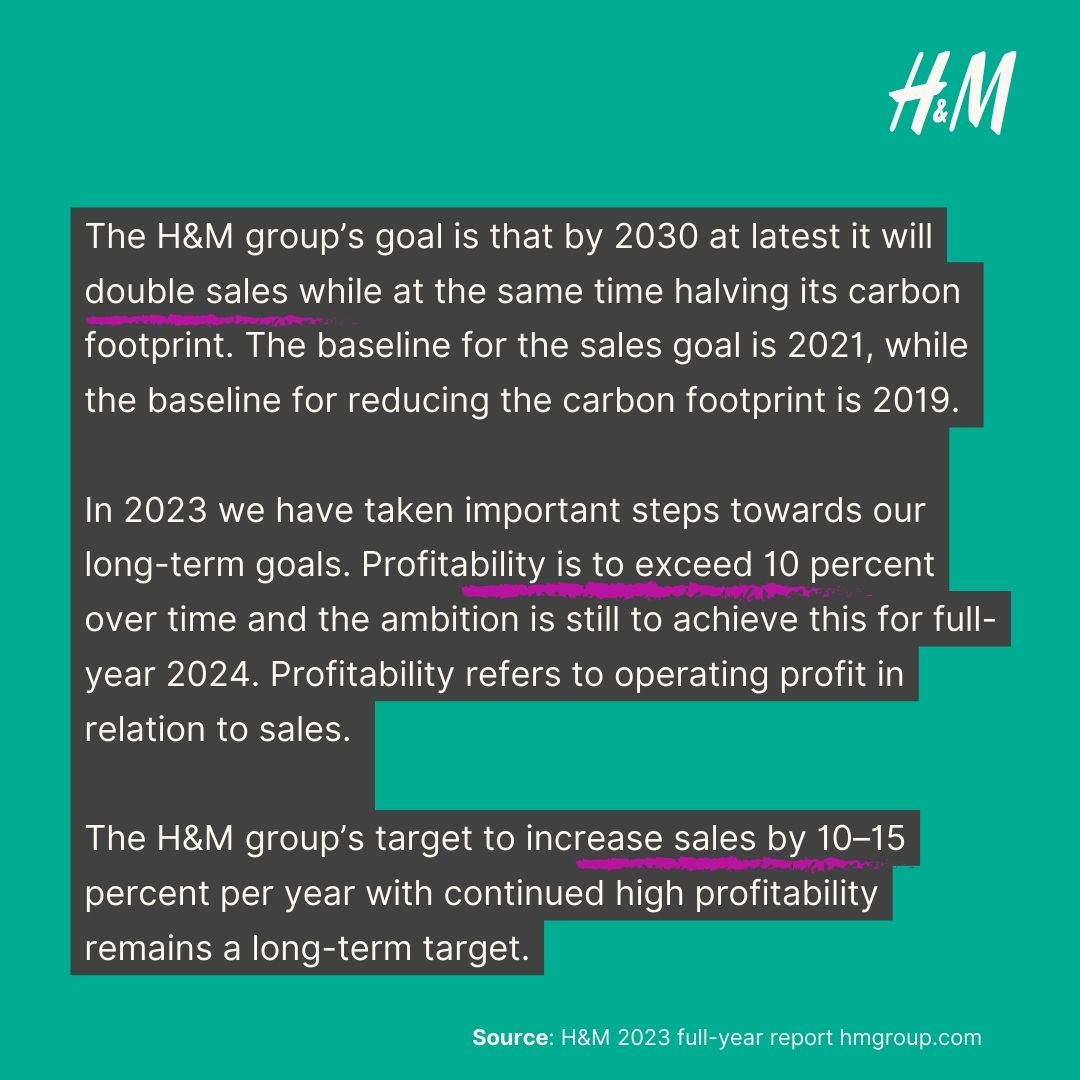

In their 2023 Sustainable Finance Framework12 they sound serious about transformation:

The textile industry faces significant environmental and social challenges. We see great opportunities to meet these challenges, but this requires major transformation of the industry as well as companies. The H&M Group has an ambition to lead the change towards achieving a circular fashion industry with net-zero climate impact. We are exploring new business models, innovating with new materials and processes, and collaborating with others to reinvent the fashion industry. (page 2, bolding my own)

But unless they stop producing clothing with degenerative raw materials, their somewhat less bad efforts are eclipsed by the growing problems. They can talk about circularity all day long, but there is no industry transformation here. There is just more clothing being produced from virgin raw materials for profit, some of which makes a pitstop through newly monetized second hand markets and additional shipping impacts on it’s way to be landfilled or incinerated as with the vast majority of clothing.13

Can H&M transform?

Newly minted CEO Daniel Ervér has his work cut out for him if transformation is to mean anything other than business as usual. Realizing this was largely drafted before he took the helm, page 14 of the 2023 annual report14 lists more than a dozen “Initiatives for an improved customer experience”, only one of which hints at circularity—

• H&M’s customer membership programme. Members receive personal fashion offers and services for an inspirational and more convenient shopping experience. Other benefits include rewards for bringing in clothes for H&M’s garment collecting, attending exclusive events and receiving other offers (bolding my own)

—while the rest are about growing sales. The targets mentioned on page 11 of the report are even more direct: double sales and increase profitability.

There are carbon reductions alongside those targets. But I’ll be very surprised if investors squawk if they don’t hit their carbon targets. And, as I have untangled previously—

—many climate indicators sprung out of a kind of alternative universe where accounting is an abstract art. I prefer to see impact in reality first, theoretical counting systems second.

Meanwhile on the shop floor

Speaking of reality, I recently dropped by a local H&M to see for myself how this garment collecting works in practice. I walked into the shop on a busy Saturday and looked around for signs of collection. Seeing none, I went up to check each of four floors (noting the escalators are designed so that I had to walk around each floor to get to the next level, making it impossible to miss the racks and racks of stuff) and saw no signage or guidance about how to participate in the circular economy.

I did see a lot of new clothes for sale. And some fake plants as décor.

Eventually I went to the cash register, passing through a gauntlet of cheap shiny pre-landfilled/incinerated accessories, where there was a somewhat unofficial looking sign about the recycling drop-off towards the end of the counter. When I inquired, one cashier explained that customers can drop off clothing. I dug for more and she confirmed with her colleague that yes they do indeed accept items from any brand. I asked what happens to those clothes being returned.

“A truck comes to get them,” she helpfully offered.

I would not describe her behaviour as that of an employee at a company with a circular business model. While there is a lot on H&M’s website about the scale of collection15, the store I visited was designed and staffed to sell gobs of new cheap stuff.

On the big flashing screens behind her there was a rotating set of ads, one of which was for H&M Rewear16. It looked a lot flashier than the bin where a little pile of dropped off clothes was stacked, waiting for a truck. But from what I can tell, that’s not reducing demand for new materials, it’s just delaying the trip to landfill or incineration while a $25 dress is now for resale for $9.25, plus $10.99 shipping.

I didn’t sense a lot of life being served there.

More to H&M’s purpose, the retail experience did not empower me to “express myself through fashion and design in a sustainable way”. Rather I felt a little depressed that this is what business model transformation passes for these days.

I asked the fake plants what they thought. They were like, “We can’t even.”

Two strategic options ahead

Right now the way H&M makes money is by increasing sales of mostly virgin fiber-based, mass-produced cheap clothing, the majority of which ultimately goes to landfill or gets incinerated.

When we compare that to what the world actually needs in terms of cloth and clothing, not to mention to repair crashing ecosystems and human wellness, that calls for a very different kind of transformation than the one they are signalling to investors now, i.e. more growth-as-usual with a few side projects, with stores full of unnecessary, unused surpluses of stuff.

To transform in service of life, the decision-makers at H&M have two distinct choices.

Option 1

They can be upfront about the current business model, and about the lack of any real plans to change it. They can own it and stop pretending it’s anything other than what it is. Investors and consumers can decide for themselves if they are okay with that.

This requires clarifying to customers and investors alike that efforts in collection and harm reduction may continue (depending on budgets), but there are no plans to stop selling way more than anyone can responsibly consume in a lifetime, because that is the business model.

That is how H&M generates profit now, and they apparently plan to continue this way until forced to stop by calamity or other cause. They can bring the cross-channel messaging into alignment with how the money flows, as indicated by the recent share buy-backs, signals to investors, and reality in their retail channels.

They can stop pretending to be transforming the actual business model.

Option 2

They can transform the actual business model.

The full wardrobe change of Option 2

In the Vision and Strategy section of the Sustainable Finance Framework document, H&M notes one of their “deepest intentions”:

Leading the change by pushing ourselves and the industry to reinvent and transform.

I love that intention. It looks like they’re interested in Option 2. Here are my recommendations for Daniel Ervér, and anybody else looking for real transformation in the apparel sector. Like any great wardrobe, it’s made of a small number of absolute essentials. Without these, no fake accessories can help.

Accept zero revenue from degenerative practices.

Measure your progress towards serving life.

Pay producers and suppliers to restore ecosystems and improve human wellness.

Let shareholders know that financial returns are no longer primary drivers of decisions.

1. Accept zero revenue from degenerative practices

Going forward there needs to be a clear, near-term strategy to end revenue streams from degenerative practices. Just as we don’t take bribes from suppliers, we don’t generate revenue from activities that undermine life.

We cannot dabble in serving life. We are either part of a healthy, mutualistic system or we’re undermining it and causing those “material issues” to be issues.

I can appreciate the resistance to this (and I offer some help with the recoil—see “Are you crazy?…” below). It’s hard to accept that what we’ve been doing can’t go on. I can relate—I came to this painful realization myself.17 We were born into a system that says accruing wealth is success, and the consequences of that so-called success have largely been blocked from our view, so rejecting it feels counter-intuitive and daunting.

But the alternative, accepting income at others’ expense (or much, much worse) is not viable. No more pretending we don’t know. We know.

It’s time to stop accepting that money, to pursue other forms of success.

2. Measure your progress towards serving life

Ensure all revenue comes from serving life.

That is probably more than a company the size of H&M can take on next quarter. But something they can take on—immediately—is ensuring they actually measure progress towards serving life. (Not the “use of proceeds” mumbo jumbo of the Sustainable Finance Framework. I mean real life. Even the fake plants know better than that.)

I’m generally leery of metrics. They can weasel us out of dealing with things (see also: the languishing Higg Index). But companies who are serious about transformation can measure serious things, such as:

Percentage of revenue from degenerative activities compared to regenerative activities.

Degree to which marginalized voices—human and more-than-human—currently influence strategic decision-making and planning. (That will help with being real about what is regenerative, by the way.)

If all of that still feels a bridge too far, perhaps H&M could start here:

Total volume of new stuff created, compared to old stuff converted to new uses, aiming for the old to out weigh the new, asap.

These are the kinds of insights that a Matereality lens brings, instead of rehashing the issues in a mainstream ESG materiality analysis. (I know those assessments are expensive, having been involved in dozens myself. For something more cost effective—free in fact—here is an open source reality-based methodology I made to serve this very purpose. I hope it fits :-) )

3. Pay people to restore ecosystems and improve human wellness

There are currently 150,000 employees at H&M, over 600 suppliers working in nearly 2000 factories. These people, along with over 4,000 physical stores18 globally and dozens of on-line marketplaces, constitute an incredible amount of talent, energy, and infrastructure.

Imagine what happens when the only things an apparel company sources, the only activities they train and pay employees to do, are intended to ensure ecosystems are improving and people are healthier.

There is an infinite array of possibilities for how a company such as H&M could achieve this. The diverse and profound voices in the supply chain and retail communities might be a good place to start. (The Deconstructing Hegemony series of Pluriversal Planet is excellent context if these ideas are new.)

There is wisdom and skill that can be honoured in ways that don’t require causing harm, to develop what comes next.

4. Let shareholders know that financial returns are no longer primary drivers of decisions

Up until now shareholders have been treated like VIPs instead of the absentee owners who don’t lift a value-creating finger that they are. This is not serving life. A wealth-extracting, rent-seeking business model gains financially by causing harm. It’s basic math.

Of course shareholders are human beings worthy of respect. In fact most people reading this are shareholders in some way or another (unless you read this and now, like me, you exited the market).

But being worthy of respect and being treated like deciders are two different things. Be transparent so they know that you are really transforming now, and it’s unclear what it means for shareholders’ returns or even existence. And while you respect them and are not wishing them ill, their well-being is not your concern.

If there is consternation, share this article about the shameless brutality from the apparel industry’s legacy, 5 Ways Imperial Britain Crippled Indian Handlooms, and ask them to thank you for not cutting off their thumbs as we reorient the norms of the day more gracefully this time. This is a true story from which they have been the literal benefactors.

Enough already.

“Are you crazy? This is totally unrealistic!”

I know to some this all sounds crazy. The reasons to not proceed in this way come tumbling at me frequently enough to anticipate them by now. Things like:

“What jobs will all these people do if we suddenly change?”—seemingly in defence of a workforce that has found its life’s work in churning out cheap, harmful stuff. This is denial cloaked in mercy.

“People need to buy clothes somewhere!” A practical point, missing that no one needs more cheap disposable clothes. This is a weak, double-edged defence of retail therapy. It avoids making space for real healing, while masquerading as compassion for people of scant economic means who are, ironically, those whose diverse textile traditions are least served and most oppressed, and whose voices are least considered in corporate boardrooms (except for coopted patterns, colours, and creative techniques).

And then there’s the tried and true: “We have to meet people where they are!” Which is typically code for, “I can’t handle what you’re saying. It’s too much.”

These—and more—are understandable reactions to an admittedly crazy proposition.

I think it’s even crazier that we have acres of retail space and vast warehouses of inventory stacked with products made with materials that harm the land and water, made by people who have a lot more to offer their communities than hunching over ergonomically compliant machinery in factories that celebrate having functional fire exits, knowing full well the majority of these net-harming, net-oppressing products will go to landfill or be incinerated.

And I think it’s unfathomably crazy that that is profitable.

Yes, we need clothes. But no one needs clothes made in that system. Most of our educational, economic, and even tax structures push us towards this crazy tear in the fabric of human society. Still, we have choices. At the very least we can be honest about what is going on and stop pretending it’s sustainable.

Souls! Redeemable! Claim yours now! Offer expires soon!

We’ll know we’re closer to where we need to be when “expressing ourselves through fashion and design in a sustainable way” means being clothed in ways that serve our purposes—comfort, beauty, character, tribe, to name a few—while restoring ecosystems and honouring the humans within them. That is cloth with soul.

No more, no less.

To paraphrase POSSIBLE FUTURES19, we cannot change empire from within empire. After numerous efforts to claim the emperor is sustainably clad, it’s time to leave him, naked, withered, and soulless while we wrap warm and comforting possibilities around ourselves.

To our delight, we may just find these outfits are sturdier and more beautiful than anything we’ve ever worn before.

Footnotes

Statistica.com “Volume by segment” including children’s, women’s, and men’s apparel = 186 billion new garments a year (last updated Feb 2024): https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/apparel/worldwide#volume

News about the effort to revive the Higg Index through a rebrand here: https://reportalert.info/3blmedianews/?mid=1251606

H&M home page: https://hmgroup.com/about-us/

H&M’s 2023 Sustainable Finance Framework: https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/HM-Sustainable-Finance-Framework.pdf

H&M’s 2022 Sustainability Disclosure: https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/HM-Group-Sustainability-Disclosure-2022.pdf

H&M’s 2023 Sustainable Finance Framework: https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/HM-Sustainable-Finance-Framework.pdf

H&M’s Q4 2023 earnings call transcript: https://seekingalpha.com/article/4666481-h-and-m-hennes-and-mauritz-ab-publ-hnnmy-q4-2023-earnings-call-transcript

H&M CEO change-over announcement: https://hmgroup.com/news/daniel-erver-new-president-and-ceo-for-the-hm-group/

Faber was apparently ousted as CEO of Danone for promoting regenerative practices. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Faber

H&M’s update on Feb/Mar 2024 share buy-back: https://hmgroup.com/news/buybacks-of-shares-by-hm-during-week-9-2024-the-share-buyback-programme-is-now-complete-and-has-been-closed/

H&M’s 2023 Sustainable Finance Framework: https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/HM-Sustainable-Finance-Framework.pdf

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future (2017) https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy

H&M’s 2023 annual report: https://hmgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/H-M-Hennes-Mauritz-AB-Full-year-report-2023.pdf

H&M’s on line customer-facing pages (as opposed to ESG documents) about closing the loop: https://www2.hm.com/en_ca/sustainability-at-hm/our-work/close-the-loop.html

H&M’s buy/sell second retailer: https://rewear.hm.com/ca-en/about

I share this story in more detail in this Dec 5 2023 talk in Toronto, Canada, On the path to Industrial Healing.

H&M’s corporate website: https://hmgroup.com/about-us/

POSSIBLE FUTURES’ video “Decolonization: Patterns and Traps”.

This is a work of art. A work of love. A richly woven tapestry of attention, love, data, insight, pun, metaphor, wisdom, experience, pragmatism, encouragement and the rest. Please tell me you have sent this to every fashion house/kingdom..