A Google search in service of life

Prototyping the use of Actual Intelligence for sustainable transformation

When a company is so big that it is also an action verb, and one that’s done billions of times each day, influencing what we buy, where we go, how we get there, and what we believe along the way, then this company has an outsized impact on our lives and our commons.

And when the goal of such a company is financial growth, while externalizing or simply ignoring most of its impacts on human and ecological health, it has a devastating impact on our lives and our commons.

Alphabet Inc, aka Google is one such company.

This piece features key insights and supporting data from the first ever Matereality assessment, which I conducted on Google in 2022 — in and for the commons — and recently updated.

A Matereality assessment is an open-source method that uses a company’s own public disclosures to show what they say they’re doing compared to what they’re actually doing, and then compares that with what is required to serve life.

We can think of Matereality as a very special kind of software: Actual Intelligence, something we are all born with and can use for free whenever we like.

The following is a quick “Matereality check” on Google using this methodology. And then, drawing on my decades as a sustainability consultant, I also provide additional insights which were revealed through the Matereality assessment, including an analysis of investor communications and stakeholder perspectives.

Matereality check: says vs does?

What happens when we look at Google through the lens of Matereality? The first question Matereality asks is: what does the company say they do? Google’s answer appears noble: their mission is to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.

We’re concerned with reality here in the Matereal World. To get at this, the second question Matereality poses is: what does the company actually do? The answer to this question is quite different. Google’s core business is advertising, across a range of on-line platforms and services. Their advertising revenues are already huge (earning over $237 billion in 2023), and they plan to do more, faster. Google sells advertising using AI and personal data to fuel consumerism and profit.

That’s what they actually do.

They have several ambitious sustainability goals and initiatives, but these don’t mention — much less pretend to reverse — the fundamental harm of the core business.

What needs to be true instead?

The third and most important question Matereality seeks to answer is: what is required of this company to serve life, to enable people and ecosystems to thrive as a result of its core business? To answer this, Matereality invites perspective from diverse international stakeholders, including human and more-than-human views. The results yield ideas about what is needed—and possible!—instead of what we have today. With that in mind what could life-affirming Google’s mission be?

When we consider an economy that serves life, a different Google emerges, one that creates a healthy commons, practices data symmetry, and incentivizes the wellness of all living systems.

Current real-life Google is nowhere close to that life-affirming mission. The following summary of the Google Matereality assessment explores:

the company’s origins compared to its current state;

a nod to the positive work underway;

three key themes with recommendations for Google to change in service of life;

bonus round: one very simple reason why AI worries me in this context.

The fine print, inspired by Google, only more symmetrical

This assessment is based on Google’s own public disclosures in their Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, investor earnings calls, and numerous other public disclosures as well as voluntary stakeholder interviews. The assessment summary, interviews recordings, and resource links are available here.

I also share many observations and writings on the subject 100% free and publicly (see links in assessment appendix). Below, I provide more detailed commentary and an audio version of this article, available for subscribers only. Subscription details (including an option to access all content for free) are available here.

My intention is to inform industry decision-making within technology and other global publicly traded firms, to ensure the lens of serving life is put in front of all else. This requires huge transformation, which I believe is both entirely possible and way more fun than the alternative.

🔲 By continuing to read this, you don’t have to consent to anything.

🔲 Comments are welcome, as are corrections.

Let’s get to it.

Once upon a time, Google was awesome

The company’s origins began in a far more commons-oriented place than where they’ve ended up today. Looking at a concept document of Google from 1998, it is heartbreakingly quaint to read the founders’ observation that, “the goals of the advertising business model do not always correspond to providing quality search to users,” followed by their belief that “the issue of advertising causes enough mixed incentives that it is crucial to have a competitive search engine that is transparent and in the academic realm.”

And it’s beyond heart-breaking to see what happened after that. The IPO letter in 2004 from those same founders included an eerie foreshadowing.

As the company switches to public ownership they describe the “important benefits for our employees, present and future shareholders, customers, and most of all for Google users.” But — and here’s the heartbreak — they knew full well and named it out loud in 2004, that, “the standard structure of public ownership may jeopardize the independence and focused objectivity that have been most important in Google’s past success and that we consider most fundamental for its future.”

Twenty years after that niggling worry about “jeopardizing the independence and focused objectivity,” fast forward to their most recent annual earnings call in which Ruth Porat, President, Chief Investment Officer, Senior VP & CFO, explains the company’s growth priorities. She notes they have the right resources behind the most important opportunities, as they focus on organizational efficiency and structure and “removing layers”, a slower pace of hiring, and headcount down year-on-year.

In Matereality terms, that vague word salad suggests that Google is doubling down on profitability by cutting costs, laying off staff, and pouring money into AI — creating a self-reenforcing cycle of over-consumption that is degrading human and ecological wellness.

And Philipp Schindler, Senior Vice President & Chief Business Officer discusses the recent success of these efforts. He cites the examples of a large U.S. big-box retailer with a 60%-plus increased ROAS (return on ad spend) and a 22%-plus increase in store traffic using the Google AI ad product, Performance Max; as well as a global fashion brand with a 15%-plus increase in shopping traffic.

Translating this update using a Matereality lens, what that means is: Google makes mass-consumption even easier and significantly more profitable for the world’s largest corporations.

In the “Business Overview” section of the most recent annual report, they note: As our founders Larry and Sergey wrote in the original founders’ letter, “Google is not a conventional company. We do not intend to become one.”

Founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin now sit on the board of what has become indeed a very conventional company, in as much as extractive, endless-financial-growth is the order of the day.

To hear this intention to being unconventional twenty years later while observing how the company has evolved, in service of what and for whom, is alarming. To paraphrase Inigo Montoya, they keep using that word. I don’t think they know what it means.

Either they’re blinded by their own financial success, confused by an inaccurate Gemini response to the prompt ‘what is a conventional company?’, or they’re quietly getting ready to transform into a truly unconventional company and they simply haven’t told us yet.

It’s not all terrible

Before I get pegged as a raging eco-fascist, hear me out. First, I recognize that Alphabet Inc. earned about $69 billion doing non-advertising things in 2023, including some so-called “Other Bets” in health care and scientific innovations that could potentially have important positive impacts. That’s a pretty big chunk of change that isn’t advertising.

Second, I am not ignoring the benefits (nor the irony) which I personally and professionally experience thanks to Google. From making it easy to find my way around new places using Google Maps, to sharing and collaborating with Google Workspace, I benefit from their tools. Heck, the first Matereality assessments were created and published using Google Slides! (I’ve switched to Canva now, mind you. But still, I benefit from Google).

Incidentally, I don’t include Google’s sustainability efforts in the “not all terrible” department because they don’t touch the real problems the assessment reveals.

As one interviewee put it, this is “the blurry line between real, holistic, decentralized community-focused sustainability vs the corporate greenwashing that exists to basically congratulate themselves. For what? Further consumption, further exploitation, further promotion of a model that is leading us into planetary collapse,” (Samantha Suppiah, a Manilla-based Southeast Asian design strategist for decolonial sustainability and regeneration.)

Google is not all bad all the time. But Google as a company is not designed to serve life, and as a result, it doesn’t. Its core business undermines life.

Advertising is the problem

In a nutshell, Google makes money through advertising. While the percentage of revenue earned through advertising is going down, it is still the lion’s share of income and it’s only set to increase based on current signals.

The year Google listed as a publicly traded company in 2004, their total revenue was $3.2 billion, of which $3.1 billion was from advertising. In their 2023 10-K filing, they reported $307.4 billion in revenue, of which $237.9 billion was from advertising.

Let me just repeat that: Two hundred thirty-seven billion nine hundred million dollars. In advertising revenue. In one year.

But wait — what’s the problem (other than it’s really hard to picture that much money)? Why is revenue from advertising bad? I sometimes even advertise my own work —

—what’s the harm in that? There are all kinds of folk contributing to a potentially life-affirming economy. Shouldn’t they tell us about their great work, too? And doesn’t it make sense to pay people for their work?

Yes, they should. And yes it does.

The problem comes when what is advertised — and growing exponentially through advertising — is causing harm. I’m not talking about companies who traffic endangered animal parts or weapons (because that goes without saying, right?). I’m talking about the runaway consumerism that is depleting our biosphere’s ability to keep us alive, in service of wealth-hoarding masquerading as progress.

That’s the problem with advertising.

Measuring the success of a company based on advertising sales is a terrifying accelerant on that problem. Throw AI into the mix and — in the words of Philipp Schindler on that earnings call once again — things are “super charged”.

Google has been describing itself as an “AI-first company” since 2016. This is an effort to signal to themselves and others that they’re doing all they can to keep up with the fast-paced tech developments around them. Unfortunately what it signals to me is that they are determined to make as much money as they can with their existing ad-based business model, using AI as a driver because it will make them more profitable, or at least keep them from losing marketshare, if they get those “resources behind the most important opportunities” as the CFO mentioned, above.

What’s to be done?

Matereality is what happens when we apply that inner software of Actual Intelligence. The prompt we enter into the human mind-machine might be something like, “What would a company like Google be doing if it existed to serve life on earth?” The responses come from a range of people who understand diverse social and ecological challenges, in some cases even speaking on behalf of very specific and important biomes.

And the responses come from giving deep consideration to the questions, even when the forthcoming answers represent a profound shift from where we are today.

Key themes for transformation

The analysis revealed three interrelated themes that need to be addressed for Google to truly work in service of life.

Its primary source of revenue — advertising — incentivizes consumerism, celebrity culture, and a westernized version of “success” which prioritizes material hoarding at the expense of human and ecological wellness.

The focus is on scaling the AI business for increased efficiency and profit, versus any data symmetry between the company and its customers, much less any regenerative or decolonial design parameters.

There is no evidence that decision-makers see the need to design the reversal of social and ecological degradation into the core offering. Hence growth is pointed in the wrong direction towards greater, faster degradation. The sustainability programs (which are ambitious compared to some corporate peers) don’t address the issues because they don’t change the core business model.

These are not trivial themes — indeed they require a wholesale transformation. But the scope of what is happening to many humans and the ecological support systems we rely on is also not trivial. So, “size of the change” can’t be the reason for inaction. Not to mention, Google has clearly created ENORMOUS change already. They can do hard things when they choose to.

A few recommendations

During the interviews numerous ideas surfaced. I have parsed a few here that are easy to summarize in an article. The interviews are open and available to inspire deeper consideration.

We imagined what would be possible if Google…

only earned revenues by cultivating wellness for individuals, communities, and ecosystems, so that no advertising revenue made it to the books without first clarifying to what end the advertiser generates their revenue;

had complete data symmetry and transparency, where providers of the data (i.e. users/consumers/everyday people) had full and easy access to how their data was used;

people from the Global South, indigenous communities, or other people who came from a pluriverse of worldviews were responsible for the AI and algorithms, and for the strategic decision-making affecting all products;

incentivized people to use their own inner “technology,” to find answers through their own real world discovery process, to explore knowledge within communities and across generations, instead of only seeking external, online sources.

It’s not possible to fully grasp the scope of what the company does with a few conversations and public disclosures — Google is large and complex. Fortunately it’s also not necessary to fully grasp everything, in order to get a sense of the direction of travel (towards more trouble!) and what is possible instead (digital commons, with wellness at the centre).

We can see important features of the business model and how it contributes to—or in this case undermines—an economy that serves life. And we can call up far better, more responsible approaches for the decision-making hearts and minds of the company to consider as they go forth, organizing the world’s data in a way that is accessible and useful.

Bonus round: one reason why AI worries me

AI worries me for a bunch of reasons. Obvious things like, who decides what the language models are, who benefits from those decisions and why, and who trains the human reviewers who are at the backend of Google’s AI interface, Gemini? There are massive potential impacts to human and planetary wellness connected to this. But people with far more sophisticated perspective on this technology than I have are better suited to offer insights on these points.

My worry is far more mundane.

I’m concerned about how brutally inaccurate the AI tools are. There are caveats about accuracy, but how much people will question basic facts is unclear, and AI is obviously being used actively by more people for more things.

Case in point, I asked Gemini how much of Google’s revenue comes from the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region. Here’s the answer Gemini served up on the first pass:

The Asia-Pacific (APAC) region is a significant source of revenue for Google, but the exact percentage can vary depending on the source and timeframe. Here's what we can glean:

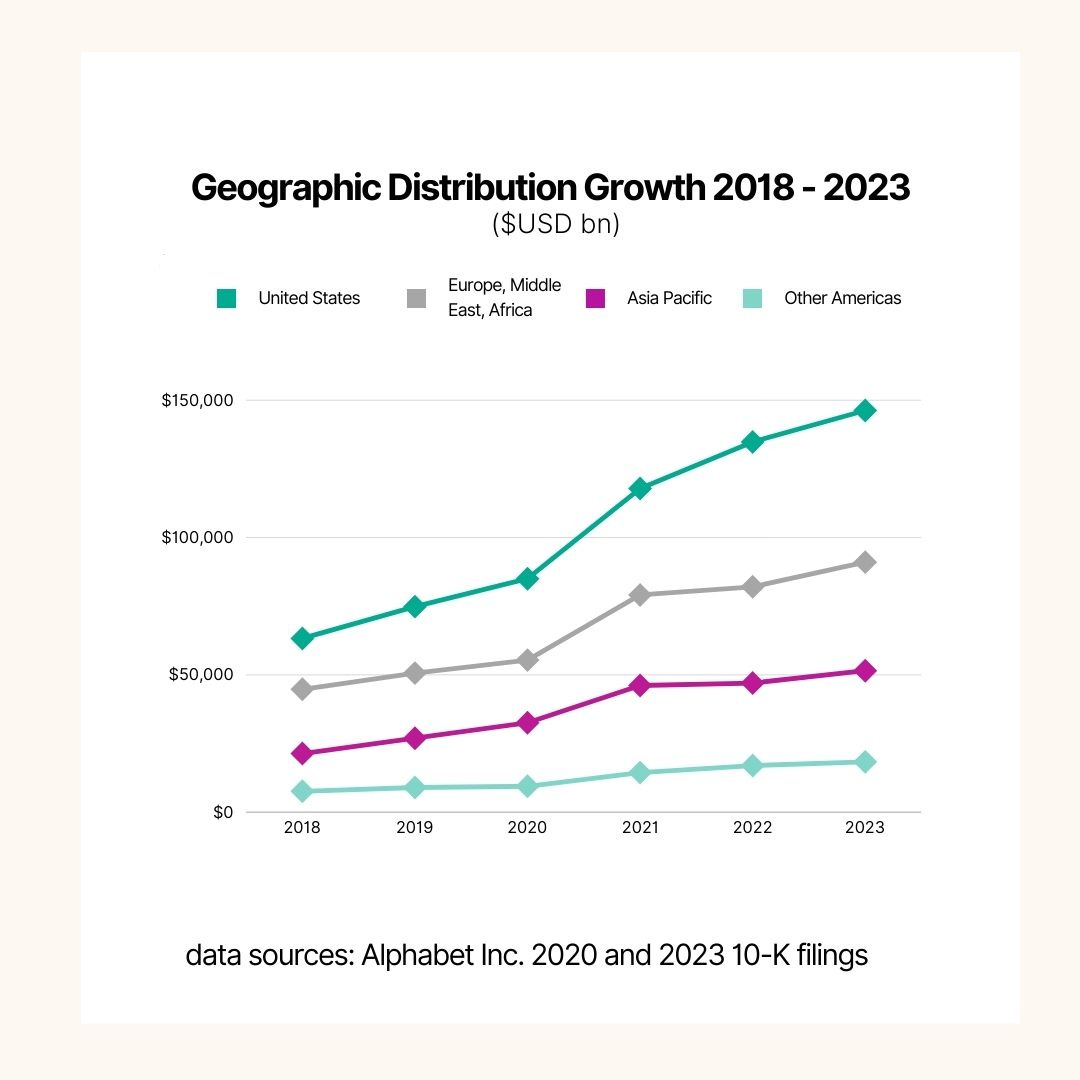

Growth potential: APAC is one of Google’s fastest-growing regions, with revenue increasing at a higher rate compared to others [3].

Estimated share: In 2023, figures suggest APAC contributed around 18% of Google’s (or its parent company Alphabet’s) total revenue [1, 2].

While there isn’t a single, definitive source for the most recent split, these figures provide a good ballpark.

A few things struck me as odd here. First of all, counter to what Gemini says, there is a definitive source: the company’s SEC disclosures, which are public and updated quarterly (and easily findable with a few human-driven keystrokes). But more worrying is that anyone using the chart generator in a Google sheet (or AI-enhanced Canva…) can see at a glance that Google’s own disclosures tell a different story:

Along with the detail of the 2023 figure being 17% not 18%, APAC is nearly the least-fast growing region according to their own disclosures. Growing, yes, but it’s not the fastest-growing. Granted, one of Google’s major AI competitors, ChatGPT was even worse, answering:

As of my last update, Google does not typically break down its revenue by specific regions like the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region in its financial reports.

To which I re-prompted with, “i think that’s a mistake — i see regional breakdown in financial reports,” and ChatGPT offered up:

You’re correct; I misspoke. Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc., does provide regional revenue breakdowns in its financial reports, including for the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region.

I’m not here to spend my days picking apart shoddy AI responses. I was legit trying to update my research for this post. But if the tool-builders aren’t building tools that answer basic questions about themselves, why on earth should we expect them to help us effectively with more pressing matters like not consuming ourselves into metabolic collapse at all scales in all regions? How about their ability to centre the knowledge and perspective of different communities?

Google says its mission is to organize the world’s data and make it accessible and useful. It seems AI is not organizing data but rather generating another less-real reality, for even more profit. This feels even further from the mission than it’s pre-2016 AI-first version of the company.

Which brings us to one of the stakeholder interviews, in which Juliana Lopes, a Brazilian climate finance professional and former journalist, reminded us the origins of the word “economy”: the management of our shared house. She dreams of the day when we get back to the meaning of this word.

As Juliana pointed out, “It’s present in us — we already have it loaded in our software. It’s just a matter of updating ourselves.”

This is us, currently downloading and debugging.

A few handy links

Here is a little clutch of handy links if you want to dig a little deeper.

Here is a link to more context about Matereality, as well as the free methodology download.

Here is a 10-minute video in which I explain the methodology.

Here is the refreshed Google Matereality assessment deck referenced above.

And here is the original artifact, i.e. the Google Slide deck of the Google Matereality assessment. (I realize that’s a bit meta. We’ll maybe talk about Meta some other time…)

Cover art painted by Montreal artist Gary Bray; image used with permission.

Your third suggestion really spoke to me. "incentivized people to use their own inner “technology,” to find answers through their own real world discovery process, to explore knowledge within communities and across generations, instead of only seeking external, online sources." This is where I'm called. Thanks for the work you do.